‘Sweet Salone’ – Sierra Leone – Africa’s hidden gem

January 26, 2018

4 Of The Best Wilderness Areas In Zimbabwe

February 13, 2018

‘Sweet Salone’ – Sierra Leone – Africa’s hidden gem

January 26, 2018

4 Of The Best Wilderness Areas In Zimbabwe

February 13, 2018

I’m breathless and perspiring, in spite of the Karoo morning chill. Two Austrian tourists and I have spent the last hour clambering up and down the steep, scrabbly slopes of Saltpeterskop in South Africa’s Mountain Zebra National Park (MZNP) in search of a collared cheetah. Up ahead — rifle in one hand, an antenna in the other — field guide Dan van de Vyver is trying his best to locate her, but the topography is wreaking havoc with his radio signal. Every time the beeps seem to be getting stronger, they fade away just as quickly as they came.

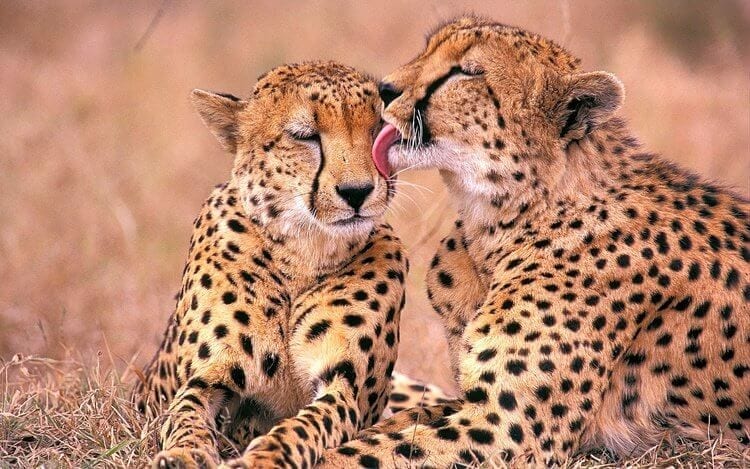

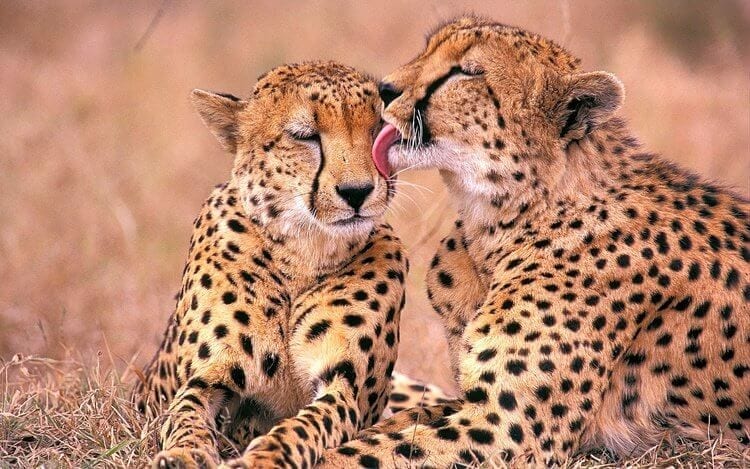

Tourists can now track Cheetah while on safari

Just when I’m starting to wonder whether or not we’ll ever find her, one of the Austrians spots her round ears poking out from behind some grass. We gaze at her from a distance of no more than 10m. At first, she just lies there, but after some time she rolls over, stands up and arches her back before strolling off into the rocks, never to be seen again. “They like to rest somewhere high, where they can see the lay of the land,” whispers Dan. “She’s probably going down to the plains to hunt now.”

Traditionally, radio-tracking large cats have been reserved for bearded PhD students and celebrities such as David Attenborough and Bear Grylls. But now tourists, too, can experience the thrill of searching for a wild cheetah on foot. By the time you arrive at reception, your safari guide will already have downloaded the cheetah’s approximate GPS coordinates from a satellite, which assists in the quest. You’ll be driven towards the cheetah in an open Land Rover until the road runs out (often accessing parts of the park that are off-limits to other visitors), before continuing the search on foot.

Experience Cheetah in their natural habitat

The excursion gives ordinary people a chance to experience what cheetah are like and how they behave. “You’re following the world’s fastest animal in its natural environment, so nothing is guaranteed,” says Dan. If the cheetah you're tracking happens to be hunting or nursing cubs, you might only glimpse it from afar, or you may even draw a complete blank. That’s just how nature works.

That said, there’s no such thing as a bad day when you’re hiking through the African wilderness with an exceptionally knowledgeable ranger. At one point, we stopped to admire a majestic martial eagle; at another, we were given an impromptu lesson on the family structure of the Cape ground squirrel. Dan even threw in a few facts of Anglo-Boer War history. Over the years, I’ve been fortunate enough to spend plenty of time doing amazing things in game reserves all over Africa, but I’ve never had an experience quite like this.

There are places in South Africa where you can walk with a semi-wild cheetah or even pet a completely tame one. This is not one of those places. MZNP’s cheetahs are wild, and their survival depends on two things: hunting enough prey to support themselves and completely avoiding the park’s male lions. No one knows more about this than Dan who, while working as a field guide, also completed his Master’s thesis on the interaction between the park’s two biggest cat species and has since been transferred to Kruger.

Cheetah in a mountainous park?

We quizzed him to find out more about this exciting subject. “Two male and two female cheetahs were introduced in 2007 to see how they would fare,” he explains. “Many people thought that cheetah wouldn’t react well to the high-altitude, mountainous habitat… but how wrong they’ve proved us all.”

Dan’s co-supervisor at Rhodes University, Dr Charlene Bissett, monitored the cheetah in those years. She soon concluded that the cheetah, in addition to being fast on the flat, goes up and down rocks and slopes smoothly and is an extraordinarily efficient and adaptable predator. “They did really well here,” summarises Dan. “So well that we’ve had to relocate quite a few to other parks.”

At first, the cheetah used around 85 percent of the park’s 284sq-km territory and preyed on a variety of species. They targeted Springbok, Kudu calves, Vaal Rhebok and Mountain Reedbuck enjoyed remarkable success rates. “Cheetah,” explains Dan, “are very meticulous hunters. Running at such high speeds burns a lot of energy, so they can’t afford to make many mistakes.”

Arch-enemies - Cheetah and Lion

Dan arrived at the park in 2013, the same year that lions were introduced, to observe the cheetahs’ reaction to this massive change in their habitat. “It’s very rare for a cheetah to be introduced to a park before a lion, and it’s never happened in a high-altitude environment such as this one,” says Dan. His thesis asked two core questions: firstly, would the cheetah change their land use because of the lion? And secondly, would their diet change now that they were no longer apex predators? “The size of their ranges didn’t change when lion were introduced, but the position of the ranges did. Before this, they used more open, sparsely vegetated areas.

Once the lion had arrived, they still preferred to hunt in open areas but used areas of thicker vegetation to rest and recuperate.” The total number of species killed by the cheetah has increased slightly, from 13 before the Lions’ arrival to 15 afterwards. Medium-sized prey (30-65kg) are still prominent, but the cheetah are also killing increasing numbers of smaller animals. “Put bluntly; they have to catch things they can eat quickly before the lion arrive.”

Three Lions introduced to Mountain Zebra National Park

When the two lions and one lioness were introduced, park staff hoped that they would form a pride. But lion play by their own rules and, after a few days, the lioness separated from the males. “My data showed clearly that whatever vegetation type the male lion were choosing, the lionesses were avoiding. And whatever the lionesses were selecting, the cheetah were avoiding. This is a classic example of what ecologists call top-down regulation.”

The study has also awarded Dan first-hand experience of lions’ opportunism: “In one five-day period the pair of male lions killed two buffalo calves, a mountain zebra stallion and an eland bull!” He’s also amazed by the lioness’s hunting prowess: “Over the year, she has killed three eland bulls, a phenomenal achievement for a lone lioness.”

Can Cheetah adapt efficiently to the presence of Lion?

Since 2013 only two — or perhaps three — cheetah have been killed by the lion. Being introduced before lion seems to have dramatically improved cheetah survival rates, observes Dan, who would expect to see similar results in other closed systems … provided conditions are favourable for cheetah and — very importantly — that lion numbers are prohibited from getting out of control. “More lion means a higher encounter rate,” explains Dan, “and would ultimately result in cheetah being killed.”

Dan’s findings prove that lion and cheetah can coexist in small parks — especially if a cheetah is introduced before the lions and if the lion population is efficiently managed. Having lion, there has changed the way that all species in the park interact. Although there was some “prey naïveté” in the beginning, “all of the animals are now much more in tune with their natural survival instincts,” says Dan, “which makes for a much more authentic tourist experience.”

Credit: Travel Africa Magazine

Contributing Author: Nick Dall